Taxing Unrealized Capital Gains: A Progressive Taxation Measure or An Irrational Taxing Adventure

- Rishi A. Kumar

- Jul 4, 2025

- 28 min read

The author is Rishi A. Kumar, a Fourth Year Student from Tamil Nadu National Law University, Tiruchirappalli.

I. Introduction:

In India, matters of direct taxation are governed by the Income Tax Act, 1961. This legislation establishes the framework for the administration of direct taxes, including the relevant authorities, procedures, and definitions. The definition of “income” which is the central subject of the Act, is provided under Section 2(24), which includes various heads of income such as “capital gains.” Section 45 of the Act further elaborates on the taxation of capital gains, outlining their types and the conditions under which they are taxed.

To grasp the concept of ‘unrealized’ capital gains, one must first understand what ‘capital gains’ means. Essentially, a capital gain refers to the profit earned from selling a capital asset at a price higher than its original purchase cost. It occurs when an asset is sold at a value exceeding its initial purchase price. Capital assets include a large range of investments, including stocks, bonds, and real estate, as well as goods that are used for personal purposes, such as jewellery or paintings. To calculate capital gains, one subtracts the original purchase price from the selling price.

Before delving into unrealized capital gains, one must also comprehend the concept of a taxable event. A taxable event triggers when a transaction takes place, resulting in taxes owed to the government. In cases of normal capital gains, the taxable event occurs at the time of the sale of the asset. When an individual sells a capital asset, the profit obtained is subject to government taxation. ‘Unrealized capital gains’ refer to the increase in the value of an asset that has not yet been sold or realized. When an asset’s current market value surpasses or declines from its original purchase price or cost basis, the difference represents the unrealized capital gain or loss.

The new tax policy proposes taxing unrealized capital gains, allowing the government to tax the rise in asset value without the occurrence of a taxable event, which essentially means they are subject to taxation even if they do not sell their assets. This expansion of the definition of income is being suggested by influential economists, such as Piketty and Zucman, primarily for implementation in the United States and Europe. However, the implementation of such a policy needs thorough economic and constituitional assessment. There is a lack of any systematic studies on unrealized capital gains. Existing research primarily focuses on the United States, however this paper will aim to conduct an analysis that includes both the United States and India.

In this regard, the paper has a two-fold objective. Firstly, to evaluate the economic impact of taxing unrealized capital gains by analyzing the feasibility of current models through microeconomics and its effects on the economy as a whole through macroeconomics. Secondly, to examine the legal and constitutional feasibility of implementing a tax on unrealized capital gains and identifying potential legal challenges.

II. Review of Literatures and Articles

Despite a clear lack of non-partisan research pertaining to this specific policy, the available resources will be thoroughly utilized to contribute to the research effectively.

Wilbur Steger in an article titled “The Taxation Of Unrealized Capital Gains And Losses”, conducts an insightful investigation into the taxation of unrealized capital gains and losses, focusing on “constructive realization” and “accrual proposals” as potential policy reforms. [i] These proposals aim to address tax avoidance concerns by reevaluating the timing of tax accountability for transferred capital assets. Steger’s study employs rigorous statistical analysis to independently explore the economic effects of these proposals. By dissociating them from other tax reforms, the research offers a clearer understanding of their potential implications. The analysis delves into issues of tax avoidance, equity considerations, and revenue generation, providing insights for policymakers and researchers. The findings of this study have significant implications for tax policy and wealth inequality. This research is particularly relevant in the context of current debates surrounding wealth distribution and tax reform. By understanding the implications of taxing unrealized gains and losses, policymakers can strive to strike the right balance between encouraging investment and ensuring an efficient tax structure.

The recent push for a policy to tax unrealized gains mirrors the ideas put forth by contemporary Parisian economists like Piketty, Zucman, and Saez. Piketty’s seminal work, “A Brief History of Equality”, goes deep into the intricate dynamics of wealth inequality and its relevance in the contemporary landscape. [ii] While the book primarily focuses on the broader idea of equality, it also addresses the justification for certain tax policies. Piketty’s work stresses the importance of progressive taxation to mitigate wealth concentration. This approach resonates with Piketty’s proposal for a global wealth tax and reinforces his call for policy measures that actively counteract rising inequality. Taxing unrealized gains could address wealth concentration, prevent tax deferral, and generate revenue for social programs. However, challenges include asset valuation complexities and potential impacts on entrepreneurship and investment behaviour as noted earlier. However, its reliance on historical data for future predictions and its emphasis on wealth taxation as a solution have faced criticism for oversimplification. The book also overlooks cultural and technological influences on inequality. While valuable in its conclusions, the book warrant consideration alongside economic and policy implications and not rhetoric which the book heavily contains.

In an article titled “$1 Trillion from 1000 Billionaires: Tax their Gains Now”, Zucman and Saez from UC Berkeley, long-standing proponents of such a tax policy, present a compelling case for addressing wealth inequality through progressive taxation. [iii] With a series of articles on the workings of this tax policy, their research sheds light on the inequities surrounding billionaires’ capital gains taxation and proposes a visionary solution to rectify the system’s imbalances. The authors reveal the staggering magnitude of untaxed gains amassed by US billionaires, amounting to a staggering $2.7 trillion out of their total $4.25 trillion worth of assets. Remarkably, during the COVID-19 pandemic, billionaires’ untaxed gains surged by an additional $1.25 trillion. To counter this tax deferral advantage, Saez and Zucman propose a novel approach – a one-time tax on billionaires’ unrealized gains. Under their proposal, all gains accumulated as of April 1, 2021, would be deemed realized, and the tax would be paid over ten years, generating approximately $1 trillion in revenue. The authors claim that this tax does not disrupt economic incentives, as it applies to past gains and does not deter future investment decisions. However, there are several problems with this study, and its economic focus is insufficient to ensure that such a tax scheme will pass constitutional muster. The paper also makes questionable assumptions about the impact of such a regulation on future investment behavior and rational expectation, both are problematic.

In another article titled “Capital Gains Withholding”, Zucman and Saez, tries to address the current issue of wealthy individuals deferring capital gains taxes for extended periods. [iv] They suggest an amendment to existing reform proposals, targeting the top 0.05% with assets exceed- ing $50 million. Their solution involves implementing capital gains tax withholding, requiring the wealthiest to prepay their taxes over ten years. Illiquid entrepreneurs can prepay using a no- risk government loan, avoiding the need to liquidate assets. Withheld amounts would be credited towards standard capital gains taxes upon asset sale, eliminating double taxation. The proposal offers resilience to market fluctuations, as the tax liability remains fixed. Additionally, it generates substantial revenue from the living, limiting potential tax refunds for the wealthy. The paper relied on the Penn Wharton Budget Model, this approach could raise $2 trillion over 2021-2030 without in- creasing capital gains tax rates. They argue that the proposal stands as a promising path to equitable tax reform, ensuring fair taxation and vital government funding. This paper however has some problems. First, the implementation of capital gains tax withholding could be counterproductive for illiquid entrepreneurs. Second, the proposal includes a no-risk government loan for tax pre- payment, but doesn’t account for the burden on cash-strapped businesses, potentially hindering growth and job creation. Crediting withheld amounts towards future capital gains taxes upon asset sale will not offer a seamless solution, considering the complexities in asset valuation.

III. Understanding Unrealized Capital Gains

The concept of implementing a tax on unrealized capital gains has gained traction among progressive tax circles on an international level. During his presidential campaign, the incumbent President of the United States advocated for the implementation of such a policy specifically targeting those with a net worth above one billion dollars. [v] Multiple suggestions and measures have been put up by specific lawmakers; nonetheless, the precise mechanisms of implementation remain a topic of ongoing scholarly debate. [vi] The policy paper titled ‘Capital Gains Withholding’ by economists Saez and Zucman is the only publication that provides a limited operational mechanism for such taxation measure. It has been cited numerous times and served as the basis for the majority of legislation proposed by lawmakers and the White House. While the current document, provides a barebones working mechanism, it lacks a strictly academic aspect since it does not go into detail the economic theories at hand.

The United States like many countries has adopted the method of taxing incomes as a method of direct taxation. It has an Internal Revenue Code which defines individuals that can be taxed and what are the kinds of capital gains that can be taxed. It states that all kinds of capital gains can be categorized into short-term and long-term capital gains. [vii] However, all these capital gains are taxed at an event knows as a triggerable event. The trigger-able event in most such capital gains taxation is the event of realizing such gains.

An example of this triggerable event can provide a better understanding of this whole process. Let us consider a hypothetical scenario where A person purchased some of stocks in a public cor- poration, valued at $100 in the year 2000. Following a twenty-year duration, the stocks are now assessed at about $1000. Though the stocks that he holds has risen in value, it has not been actualized. Taxation on a capital asset is contingent upon its realization, as the increase in value is considered speculative until the asset is sold in the market and generates income for that individual.

The definition of speculative asset here does not deal with the economic definition which deals with assets of considerable volatility, however, a legal definition is used which deals with assets whose value has not been actualized through market transactions. Consequently, upon the sale of the shares at a value of $500 after a period of five years, the capital assets will be effectively recognized, thus initiating the occurrence of a taxable event. The triggering of the event allows things to be under jurisdiction for direct taxation policies of respective governments. This is where the situation becomes complex. The unique nature of unrealized capital gains lies in its attempt to tax an estimation rather than a concrete reality. The challenge emerges from the absence of a clear triggering event for taxation. The policy paper proposes a mechanism as follows: billionaires would be required to disclose the value and basis of their assets and liabilities, categorized systematically and the net worth, calculated by subtracting liabilities from assets, would be the determinant for tax assessment. Tax would be levied on the unrealized gains that if realized would result in taxable capital gains income.

The complexity arises from how the taxation event is initiated within this proposed mechanism. The policy paper suggests a statutory measure where the asset realization has not occurred in reality but is deemed to have taken place. However, the specifics of how this event is triggered remain ambiguous in their policy paper. In this context, the term ‘deemed realization’ is introduced to describe this scenario. It states: “All the unrealized capital gains of billionaires would be deemed realized and would face the top tax rate on capital gains.” The method by which billionaires make their tax payments is designed to occur gradually over a period of ten years through yearly installments, with an additional surcharge applied for the choice to defer these payments.

The policy paper, pertaining to the conceptualization and functioning of this model, jumps over this particular aspect. Instead, it indicates the adoption of the ‘expatriation model’ utilized by the Internal Revenue Service under Section 877 and Section 877A of Internal Revenue Code. This expatriation model relies on the application of the mark-to-market valuation to derive the fair-market value of these assets, thereby facilitating the assessment of unrealized capital gains. [viii] As the name suggests, the expatriation model is made to be applied only to citizens who are renouncing their citizenship. However, the article lacks any further explanation of the endogenous and exogenous factors that may impact the tax policy when operationalized. The policy, though heavily untested, has been consistently put forth by progressive legislators in their campaign circles.

The policy proposal necessitates an objective evaluation from two distinct perspectives. Firstly, it calls for an economic analysis of potential changes, including the alterations in incentives and challenges related to the valuation of unrealized gains. The chosen method of asset valuation will not be able to take into account the intricate nuances that could arise if the policy is fully implemented. Secondly, it must be scrutinized within the existing constitutional and statutory frameworks by considering judicial interpretations of the government’s authority to levy taxes on such gains under direct taxation.

IV. Economic Analysis of Taxing Unrealized Capital Gains

The nature of economic analysis of any public policy measure, particularly of taxes starts with a simple assumption. Individuals are rational in their decisions and act in the interest of their own self. Therefore, the paper will look at it from three perspectives. First, looking at the policy from tax payers’ perspective, the paper will deal with the changes in incentive structures that can occur due to taxation of unrealized capital gains. Second, the nature of a tax policy is that it applies to individuals in a broad manner and has various macroeconomic consequences for the nation as a whole, especially when it is applied to high net worth individuals. Therefore, the paper will also look at the macroeconomic effects of such a policy over a short term and over a long term period. Third, the levying of taxes is a sovereign activity that can only be conducted by the government of the time period. Therefore, the third entity to be understood is the government or more particularly the administrative side of such a policy and its implementation.

4.1 Tax Payer Perspective

The fundamental nature of not trying to tax capital gains has been thoroughly established in main- stream economics because the function of having capital is to incentivize individuals to invest their capital. This is the economic engine upon which most modern economies run on: providing avenues for investment of capital and incentivization of such activities by not taxing them. [ix] However, this does not mean that capital gains ought not be taxed. There exists no argument to support this conclusion. Capital gains that occur can be taxed but only when it is realized and the estimated fair market value is actualized through sale of such capital assets. However, the current policy runs counter to established economic studies. It tries to tax unrealized capital gains. [x]

When looking at the nature of any tax through a microeconomic perspective, there exists an artificial imposition of costs. Costs shy away from any rational actions unless the benefits of taking such costs is higher. The nature of assets of capital gains is such that they are tied up in investments, business and real estates. The rational expectation held by these individuals is that when their capital is invested, they are producing value and generating returns. Additionally they are not being subject to taxation until they are realized allowing their investments continue to generate gains and be in market circulation.

If the policy of taxing such investments is put in place, there will grow a matter of indifference in matters of savings and investment. There might even occur a skewed incentivization that promotes more careless spending as there are even proposals for closing the stepped-up basis tax exemption which allows heirs to inherit the capital gains with all the gains being reset. Therefore, the move to tax unrealized capital gains is going to disincentivize individuals from engaging in long term taxation, as the expectation will be that: the more they are letting their investment grow, the higher they are going to be taxed. This is precisely the reason as to why capital gains are taxed at a lower preferred rate rather than actual rate at which household income is taxed at.

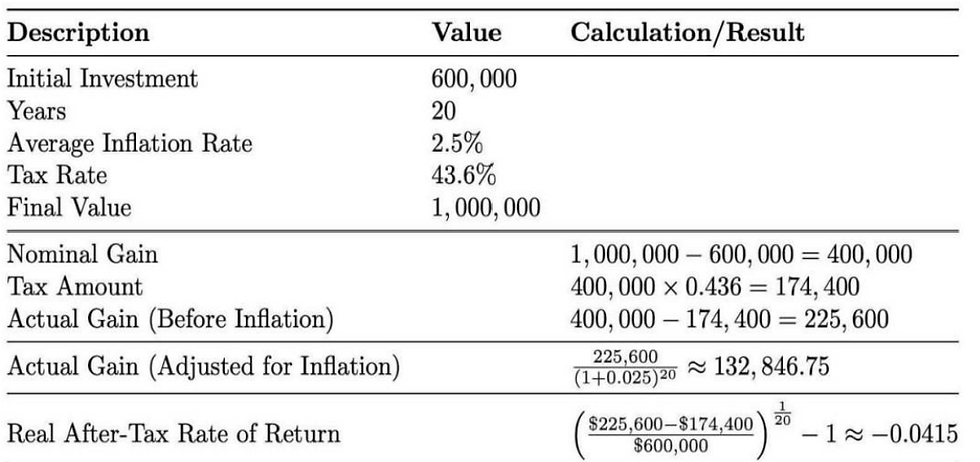

However, the most important reason as to why such capital gains taxation is kept lower is to account and adjust for inflation. As it is popularly stated the greatest enemy of any kind of wealth is inflation as it reduces the value of any kind of wealth without us doing anything. [xi] The effect of inflation on capital gains can be understood when looking at it long term and then taxing it according to the proposed 43.6% taxation on capital gains. Consider an individual who initially invested $600,000 in a set of stocks from a company. Over a span of 20 years, an inflation of 2.5% year-on year and a general appreciation market has propelled the value of the stocks to $1,000,000. Throughout this period, the individual hasn’t sold the stocks, rendering these gains as unrealized capital gains. The complexity arises in distinguishing between gains resulting from monetary inflation, demand-pull inflations inherent to specific markets, and actual appreciation of the real estate sector. While taxing these gains, it’s infeasible to separate these contributing factors effectively. Administratively, the gains are typically subjected to taxation by directly subtracting the selling price from the cost price of the asset. This is not viable when it comes to taxing unrealized gains as the value remains a mere estimate, yet they are deemed as realized. Following would be the the effect of inflation and taxes:

The results of the calculations themselves show the actual nature of such taxation policy on an average return of investment. Accounting for inflation and appreciation in the market, the real after-tax ROR is not even zero, it yields a loss of -4.15%. While the presented scenario is purely hypothetical, empirical evidence supports similar assertions and findings, as demonstrated by analysis of investment data from the S&P 500 indices. [xii]

This serves to reinforce earlier statements. The imposition of any tax is an artificial cost on market forces and it creates skewed incentive structures. The imposition of such a high cost has the effect of squeezing capital from two sides: the investors must outpace year-over-year inflationary increases and also bear a high tax rate, with the unorthodox aspect being that all of these calculations must be based solely on the speculative appreciation of assets. This is precisely the reason as to why even realized capital gains are taxed lower than the actual income tax rates known as preferred tax rates. From a tax-payer’s standpoint, the taxing of unrealized capital has two main effects. Firstly, it discourages individuals from engaging in investments. Secondly, it undermines the essential purpose of individuals investing if they are unable to outperform the average annual inflation rate. Although this measure may not appear very hazardous from an individual standpoint, its severity is acute from a macro-economic perspective.

4.2 Macro-Economic Perspective

The study of macroeconomics takes a broader view of how the economy as a whole will react to changes in it, yet it still retains the fundamental assumptions of economics. Through this per- spective, the paper will try to look at how such a tax policy will affect macro-economic indicators such as GDP, Wages and Employment rate. For such an analysis, the paper uses a study conducted by Baker Institute of Public Policy at Rice University. The authors of the study utilize a Zodrow-Diamond General Equilibrium Model that has been fitted with US economic indicators. [xiii] The model is designed to represent how households and firms behave in an economic system. Households are maximizing utility and firms maximizing firm value. The model tries to track how changes in tax policy over time are being responded to, including both short-term and long-term impacts. The model eventually converges to a general equilibrium over the long term and this is defined by a predetermined growth rate. In this state, the various elements within the economic system interact with each other in a way that maintains a steady state over a long period of time.

The model’s non-dependence on relative values is a double-edged sword. It allows for a clear examination of different variables in action, however, this model does incorporate inflation which tracks the rise in price levels due to distortionary effects. The simulation from the Zodrow-Diamond Model derives a percent change which is calculated against the growth rate that would have existed with no tax change in each year for the said variable.

The simulation results show that there is clear fall throughout the metric. The most destructive variable being found other than the obvious declines is the Employment Hour variable. This reduction in labor hours is indicative of a slowdown in economic activity or a decrease in the demand for labor. To provide a contextual example, if we were to keep the number of hours worked per individual constant, that is assuming each individual continues to work the same hours as before, the effect would be analogous to the loss of nearly 300,000 jobs within that year. As it has been stated earlier the model deals with non-relative values and this does not allow it to take into consideration the effects of inflation. The manual addition of inflationary effects in the calculation of real-values allows derivation of an acceptable nominal-values table. But, it is quite clear that inflation will only amplify the clear negative effects of this policy at a macroeconomic scale.

4.3. Administrative Perspective

The most complicated perspective to understand is the Administrative perspective. The govern- ment when implementing a tax policy usually has concrete academic backing and administrative workforce to enforce a tax policy, however, it is simply not the case here. The policy paper by Zucman et. al. provides no concrete answer to this. They simply state that the IRS currently administers around 5000 estates who are of high net-worth and adding a 1000 Billionaires is not going to be hard for them to administer. This assessment gravely misses the acute nature of such a tax policy. Leaving aside the laborious nature of this tax policy on the IRS, it is burdensome on the government due to three particular issues. First, the issue of valuation of assets. Second, the issue of payment on unrealized gains. Thirdly, the issue of capital losses. Although the three issues are dealt with briefly, the acuteness of the problem will be shown.

The Issue of Valuation is that it is based on the assumption that these assets held by these individu- als are assets that can be easily converted into cash. Though the assumption put forth in the policy paper is that a Mark-to-Market method will be used for determining fair value. Unlike stocks and bonds which are constantly driven by market forces, most such assets such as real-estates and collectibles are illiquid and determining their fair-market values are not that straightforward. If the responsibility for evaluating asset values lies with the government, it could result in a continuous cycle of disputes on the actuality of such assessment and whether it would equal the market forces. Conversely, if taxpayers are entrusted with assessing their own asset values then it leads to them undervaluing their own assets for reducing tax liability or even evasion. The main contention of this paper is that asset values should be determined solely by the market, and taxation should only occur when these values are actually realized. This is because of the speculative and unpredictable nature of asset values while they remain unrealized.

This leads us to the Issue of Payment. As stated earlier, the nature of assets held by high net-worth individuals are illiquid in nature and hard to value. They are in the form of businesses, artworks and collectibles and real estate. They cannot be converted quickly. This process of holding liquid assets and putting them into illiquid assets for investment and vice versa is a process known as maturity transformation (commonly used in Banks). [xv] The process by its very nature needs time as an essential factor, without which the assets are not convertible and may end up even resulting in economically wasteful consequences. [xvi] The nature as to why individuals use banks is to allow for maturity transformation yet still have the ability to switch back and forth by utilizing the risk-diversifying nature of banks. [xvii] However, the effect of such a tax policy is to require individuals to act like banks by engaging in maturity transformation where there is a conversion of long-term, illiquid investments into short-term liquidity without the benefit of risk diversification that banks enjoy. When individuals are taxed on unrealized gains, they are effectively compelled either to find liquid funds elsewhere or to sell capital assets to meet their tax obligations. The problem is that illiquid investments typically require careful timing and strategy when sold; forced or premature sales can lead to economic inefficiency and wastage of resources. During tax season, financial markets can experience artificial inflation caused by accelerated selling of capital assets. This would lead to prolonged unpredictable price fluctuations. Simply put, the billionaires may lack sufficient liquid cash to pay taxes, and forcing them to do so could trigger sharp, unnatural movements, potentially causing a downturn.

The Issue of Capital Losses is a very simple hypothetical question that might not be answerable. The nature of any kinds of gains and losses as has been established in tax is that losses are also considered part of income and usually an individual can offset their losses by carrying forward such losses. The same concept is assumed to apply to this tax policy. Billionaires while holding capital assets do no merely make gains they incur losses too as it is also part of any risk associated in investment. The nature of markets are volatile, though on the long run they have a steady positive growth rate, the short term has lots of volatility. The question will arise that if the individuals are being taxed on unrealized gains will they be provided with tax write-offs and refund checks when there occurs unrealized capital losses. This is precisely why capital gains are taxed after actualization of those gains through sale because it mitigates all three issues. It mitigates the valuation problem as the market forces will decide the fair value of such an asset. It mitigates the liquidity problem as through the sale of such a capital asset, there will be an actual income which can be paid in taxes. It also mitigates the Capital Losses problem as the worry of volatility of assets will simply not arise. The taxing event is triggered and the transaction is recorded in constants without any need for accounting for losses.

In summary, the economic analysis of this tax policy suggests that from the perspective of individual taxpayers, it could hinder investment opportunities and potentially lead to economic losses due to not outpacing inflation. On a macro-economic scale, the wealth of high-net-worth individuals has substantial ripple effects on GDP, employment, and wages and the simulations suggest that over the long term, this policy could result in a decline across all these economic variables. From an administrative standpoint, challenges arise in valuing illiquid assets and their unrealized gains. The issue of insufficient liquidity to cover high tax payments can lead to price fluctuations, and there still exists the unanswered question about addressing unrealized capital losses in the future. These considerations underscore the complexity and shortcomings of such a proposed tax policy.

V. Legal Analysis of Taxing Unrealized Capital Gains

The economic viability or non-viability of a tax policy does not restrict or promote a government in achieving its objectives. As Thurgood Marshall once stated: “A bad legislation is still a legislation”. The government is only bound by laws made by its legislatures and the fundamental governing instrument of modern nation-states, namely, the Constitution. Therefore, the nature of this policy ought to be tested on the anvil of the US Constitution. For this purpose, one can consider a hypothetical legislation that will be passed by the Congress based on the recommendation of a policy paper. The hypothetical legislation deems unrealized capital gains of high net-worth individuals to be income and therefore it is to be subjected to taxation. [xviii]

The United States Congress earlier derived power for taxation from the constitution, but it was subjected to heavy restrictions and did not allow for any taxation measure unless it fulfils the apportionment clause in the Sixteenth Amendment. The earlier existing clause was an equity measure provided in the taxation process which made sure that taxes collected from each state are in proportion to the population of the state. However, as the concept of income taxes on capital assets began to popularize in the late 1800s, this clause was extended to income generated from personal property by the Supreme Court in Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan & Trust Co. and struck down any income tax provisions that did not follow the apportionment clause. [xix]

Subsequently, to overcome this bar, the Congress amended and ratified the Sixteenth Amendment which now granted Congress the power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any census or enumeration that was held as mandatory. [xx] The post-ratification history of the Sixteenth Amendment demonstrates that the Supreme Court has consistently favored a textual interpretation of tax laws, avoiding interpretations that deviate from the clear language. Congress, too, has largely adhered to the original intent and textual framework of the Amendment when defining “income” in the Tax Code and subsequent legislation. Additionally, the Court reaffirmed that the Sixteenth Amendment requires a realization event as a necessary condition for any gain to be classified as income As discussed in earlier chapters, the realization event serves as the trigger for tax liability. Since realization is an essential and inseparable component of income, any gain lacking such an event cannot constitutionally be considered income.

In the case of Eisner v. Macomber, the Court tried to look into a situation where shareholders in a company were given extra shares in a stock-split situation. [xxi] Though the number of shares had increased, the actual value of the shares remained the same. The court held that increase in shares went hand in hand with the dilution in value. However, while establishing the ratio of the case, the court as a corollary also held that unless there has been distribution of dividends by a company, mere increase in value of the company’s shares does not result in income. The court has established that rule again and again.

In Helvering v. Horst, the Court continued according to its earlier precedents that income is taxable upon realization. [xxii] The case involved a father gifting interest coupons from a bond to his son while retaining the bond and the right to its principal at maturity. The question was whether the father could be taxed for the interest paid to his son from the coupons. The Court ruled that the father could be taxed, establishing the principle that taxpayers can’t avoid taxation by assigning income they would have received. The Court stated that when taxpayers can benefit from property through an event other than direct receipt of money, it constitutes income realization. In this case, the realization event was the gift of the interest coupons, emphasizing that assigning the right to another person still triggers a taxation event. In the case of Commissioner v. Glenshaw Glass, the court again highlighted the inseparability of realization and the definition of income under the Sixteenth Amendment. The case introduced a pivotal three-pronged test, requiring taxpayers to have received “undeniable accessions to wealth, clearly realized, and over which the taxpayers have complete dominion.” [xxiii] More recently, the Supreme Court had a constitutional question, very similar to the one that is being dealt here in the case of Moore v. United States, where the constitutionality of taxing provisions like repatriation taxes were questioned. However, the Supreme Court decided to defer questions on realizations for a later date, and decided the matter on technicalities.

However, a faithful application of older precedents should effectively guide the direction of judgment. The question at hand for such a court holds fundamental importance, as it directly pertains to well-established interpretations of the Sixteenth Amendment. This scenario touches upon the core interpretations of this amendment that have been upheld over time. The present composition of the Supreme Court has consistently displayed a penchant for exploring the original intent of constitutional provisions when addressing interpretive challenges. The original meaning of Sixteenth Amendment does not appear to encompass a definition of income that includes unrealized income. Therefore, the current policy in action, if implemented accordingly through a statutory change in the Federal Revenue Code, will in all probability get struck down as unconstitutional as going against established precedents and the original meaning of the Sixteenth Amendment.

VI. Taxing Unrealized Capital Gains: Viability in India?

Though the policy of taxing unrealized capital gains is unnamed in Indian policy circles, India has not been shy to progressive taxing policies and taking bold steps in promoting equity measures. [xxiv] However, the nature of the Indian economy has a much different structure than that of the United States purely because of the nature of capital assets in India. Diverging from developed nations, capital gains in developing countries like India is that they primarily arise from real estate sales. In developed countries such as the United States securities transactions take precedence. This distinction is underpinned by two key factors: the concentration of wealth tied to real estate and the prevalence of foreign corporations dominating local markets and being taxed abroad. [xxv] However, the economic analysis conducted for capital gains in the United States still applies to India, primarily because the analysis, excluding the macroeconomic section, is data neutral and based on microeconomic analysis. But the constitutional analysis and consequently the viability of such a policy as a legislative measure is starkly different.

The primary provision that provides power for taxation to the Central and State authorities is derived from Article 265 of the Indian Constitution which states that no tax shall be levied or collected except by authority of law. The nature of it purposefully kept vague to allow for more control to the parliament in regards to structuring and application of various tax policies. The only restriction therefore imposed by the constitution in regards to tax is that it ought to be done under the authority of law.

In the case of S. Gopalan v. State of Madras, the court defined ‘authority of law’ as legislative competence and should exercise only the creation of valid law. [xxvi] This when expanded on creates an obvious restriction that it cannot violate the fundamental rights and this was exactly held in Moopil Nayar v. State of Kerala. [xxvii]

The matter of taxation has established certain practices that ought to be given consideration in any tax policy and they are known as the canons of taxation and the same was held to be mandatory criterion in Shakthi Kumar v. State of Rajasthan.

The canons of taxation, as propounded by Adam Smith, consist of four primary principles: the canon of equity, the canon of convenience, the canon of certainty, and the canon of economy. A policy that imposes taxes on unrealized capital gains may conflict with the canon of convenience. As discussed earlier, taxing illiquid assets undergoing maturity transformation often requires the forced liquidation of such assets. If not executed carefully, this can lead to economic inefficiencies and resource wastage, thereby undermining the principle of convenience. From an administrative perspective, as examined in the previous chapter, the cost of enforcing such a tax regime is also likely to be significant. While it may be argued that the high net worth of affected individuals could offset these costs, the implementation still raises serious concerns.

From a constitutional standpoint, the viability of such a tax can certainly be debated. However, it may still be permissible under the current provisions of the Indian Constitution. This contrasts with the position in the United States, where the definition of income is closely tied to the Sixteenth Amendment, both textually and historically. In India, by contrast, Article 265 provides a minimalistic framework for taxation powers, granting the legislature broad authority with limited constitutional constraints. This structural difference grants Indian lawmakers greater flexibility in defining and taxing income, including potentially taxing unrealized gains.

In India, matters of direct taxation are governed by the Income Tax Act, 1961. This legislation establishes the framework for the administration of direct taxes, including the relevant authorities, procedures, and definitions. The definition of “income” which is the central subject of the Act, is provided under Section 2(24), which includes various heads of income such as “capital gains.” Section 45 of the Act further elaborates on the taxation of capital gains, outlining their types and the conditions under which they are taxed. Currently, taxation of capital gains is triggered by the occurrence of a “transfer,” and unrealized short-term or long-term are not subject to taxation.

This paper proceeds on the assumption that both in India and the United States, there may be statutory revisions to the definition of income and the associated provisions triggering a taxation event. In the Indian context, the feasibility of implementing a one-time taxation measure, particularly on unrealized gains, would likely require a separate piece of legislation adopting the procedural framework of the existing Income Tax Act. Such standalone legislation could help mitigate challenges arising from interpretational ambiguities. However, this may still raise legal and constitutional concerns. In particular, issues relating to the treatment of capital losses under such a regime, and the inability to carry them forward or offset them under the new framework, may lead to claims that the legislation violates the canons of equity and efficiency.

VII. Concluding Remarks

On the economic front, this paper analyzes both the microeconomic and macroeconomic implications of the proposed policy. It finds that while the policy may offer symbolic appeal to progressive agendas, its tangible economic benefits are limited. The analysis reveals significant downsides, including potential negative impacts on GDP growth, individual purchasing power, and overall employment. Notably, the policy is projected to contribute to a relative loss in wealth equivalent to loss of approximately 300,000 jobs in the long terms. Furthermore, the substantial administrative burden and costs involved in implementing such a measure is immense. These costs are likely to be compounded by uncontrollable variables and escalating operational expenses, casting further doubt on the policy’s long-term economic and fiscal viability.

Turning to the legal front, this paper examines whether the proposed policy of taxing unrealized capital gains can be implemented solely through statutory means, within the limits imposed by constitutional frameworks. It identifies a fundamental connection between the concept of income realization and the definition of income under the Sixteenth Amendment, ultimately concluding that a purely statutory route is legally untenable in the U.S. context. While a constitutional amendment could, in theory, enable the adoption of such a policy, the political and procedural hurdles make this option highly improbable. In contrast, the Indian constitutional framework presents fewer legal barriers. The broader and less restrictive language of Article 265 allows the legislature greater flexibility in defining taxable income. Nevertheless, the paper argues that, even in India, the economic consequences of such a policy, particularly its impact on investor behavior, are likely to mirror those anticipated in the United States. Simply put, taxing unrealized capital gains is micro-economically flawed, macro-economically detrimental, and statutorily unviable in both jurisdictions.

In response to these findings, this paper suggests taxing consumption rather than unrealized gains. This alternative mechanism aims to address wealth accumulation strategies by instituting taxation triggers during transactions with readily available liquidity for high net-worth individuals. By shifting the focus from taxing unrealized gains to consumption, the policy could potentially mitigate the widely criticized “buy, borrow, die” strategy associated with wealth accumulation.

Citations

[i] Wilbur A Steger, ‘The Taxation of Unrealized Capital Gains and Losses: A Statistical Study’ (1957) 10(3) National Tax Journal 266.

[ii] Piketty, Thomas. A Brief History of Equality. Harvard University Press. 2022

[iii] Emmanuel Saez & Gabriel Zucman. ‘How to Get $1 Trillion from 1000 Billionaires: Tax their Gains Now.’ (2021) The Econometrics Laboratory: UC Berkley.

[iv] Emmanuel Saez, Gabriel Zucman & Danny Yagan. ‘Capital Gains Withholding.’ (2021) The Econometrics Laboratary: UC Berkley. 2021.

[v] Greg Leiserson & Danny Yagan, ‘What Is the Average Federal Individual Income Tax Rate on the Wealthiest Americans?,’ (2021) White House Written Materials.

[vi] See, Ron Wyden. Billionaires’ Income Tax Act Proposal. 2021; See also, Chris Van Hollen et. al. Sensible Taxation and Equity Promotion (STEP) Act. 2021.

[vii] Internal Revenue Service. Topic No. 409, Capital Gains and Losses.

[viii] Corporate Finance Institute Handbook. ‘Mark to Market – Overview and Importance.’ (2022).

[ix] Nicholas, Tom, VC – An American History (hardcover ed.). (2019) Harvard University Press.

[x] Garrett Watson & Erica York, ‘Proposed Minimum Tax on Billionaire Capital Gains Takes Tax Code in Wrong Direction’ (2022) Tax Foundation Working Paper Series.

[xi] Henry Hazzlitt The Inflation Crisis, And How To Resolve It. (1978)

[xii] John W. Diamond. ‘The Economic Effects of Proposed Changes to the Tax Treatment of Capital Gains.’ (2021) Baker Institute for Public Policy - Working Paper Series.

[xiii] George R. Zodrow, and John W. Diamond, “Dynamic Overlapping Generations Computable General Equilibrium Models and the Analysis of Tax Policy.” (2013) In Dixon, Peter B., and Dale W. Jorgenson (eds.), Handbook of Computable General Equilibrium Modeling, 743– 813.

[xiv] Supra note 17. p. 12.

[xv] Diamond & Dybvig, ‘Bank Runs, Deposit Insurance, and Liquidity.’ (1983) (91)3 Journal of Political Economy. 405-406.

[xvi] Ibid. pp. 402-403.

[xvii] Ibid. pp. 417-418.

[xviii] Supra note 4. p. 03

[xix] Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan & Trust Co., 157 U.S. 429 (1895).

[xx] U.S. Const. amend. XVI.

[xxi] Eisner v. Macomber, 252 U.S. 189 (1920)

[xxii] Helvering v. Horst, 311 U.S. 112 (1940)

[xxiii] Commissioner v. Glenshaw Glass Co., 348 U.S. 426 (1955). pp. 348.

[xxiv] The World Bank. Implementation of India’s Goods and Services Tax. (2018).

[xxv] J. Amatong. Taxation of Capital Gains in Developing Countries. (1968) International Monetary Fund.

[xxvi] S. Gopalan v. State of Madras. AIR 1958 Mad 539

[xxvii] Kunnathat Thatehunni Moopil Nair v State of Kerala, AIR 1961 SC 552.

[xxviii] Shakthi Kumar v. State of Rajasthan. 2002 SCC OnLine SC 2691.

References

Amatong, Juanita. Taxation of Capital Gains in Developing Countries. International Monetary Fund Staff Papers, vol. 15, no. 2. 1968. pp. 344-386.

Nicholas, Tom, Venture Capital – An American History. Harvard University Press. 2019.

The World Bank. Implementation of India’s Goods and Services Tax : Design and International Comparison. The World Bank Group, Washington. 2018.

Douglass Diamond and Philip Dybvig, “Bank Runs, Deposit Insurance, and Liquidity”. Journal of Political Economy. vol. 91, no. 3. 1983.

John W. Diamond, “The Economic Effects of Proposed Changes to the Tax Treatment of Capital Gains” Baker Institute for Public Policy, 2021.

Leiserson, Greg, and Danny Yagan. “What Is the Average Federal Individual Income Tax Rate on the Wealthiest Americans?” White House Materials, 2021.

Magness, Phillip. “The Unconstitutional Tax on ‘Unrealized Capital Gains’.” Commentary - Inde- pendent Institute, March 14, 2023.

Saez, Emmanuel, Gabriel Zucman, and Danny Yagan. “Capital Gains Withholding.” and “How to Get $1 Trillion from 1000 Billionaires: Tax their Gains Now.” Econometrics Laboratory: University of California, Berkeley, 2021.

Steger, Wilbur A. “The Taxation Of Unrealized Capital Gains And Losses: A Statistical Study.” National Tax Journal, vol. 10, no. 3, 1957, pp. 266–281.

Wamhoff, Steve. “The Billionaires’ Income Tax Is the Latest Proposal to Reform How We Tax Capital Gains.” Institute of Taxation and Economic Policy, 2021.

Watson, Garrett, and Erica York. “Proposed Minimum Tax on Billionaire Capital Gains Takes Tax Code in Wrong Direction.” Tax Foundation, March 2022.

Zodrow, George R., and John W. Diamond, 2013. “Dynamic Overlapping Generations Computable General Equilibrium Models and the Analysis of Tax Policy.” In Dixon, Peter B., and Dale W. Jorgenson (eds.), Handbook of Computable General Equilibrium Modeling, pp. 743–813.

Comments